May 07 | 2020

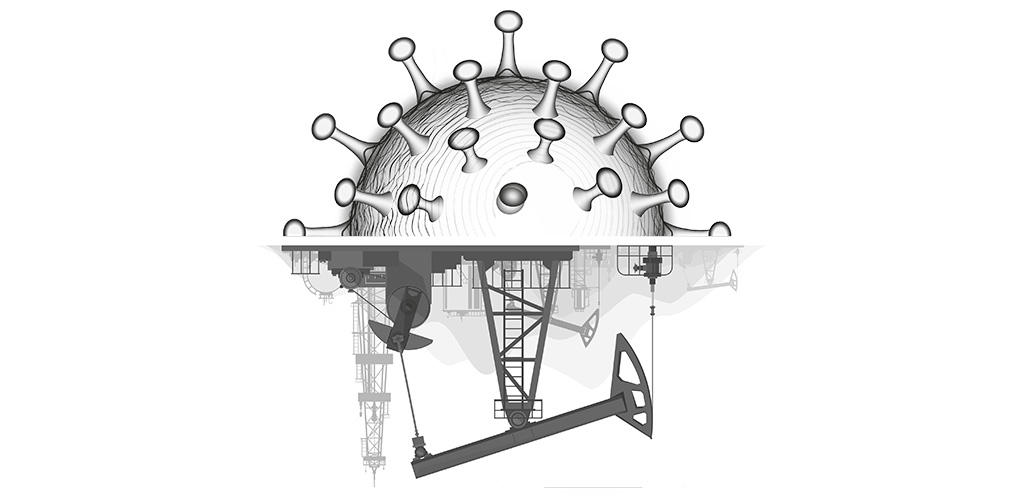

Energy Outlook Turned Upside-down by Coronavirus

By Amy McLellan

BREAKBULK ISSUE 3 / 2020 – COVER STORY – Breakbulk’s 2019 Global Energy Outlook had a clear message: “More energy, fewer emissions.” Twelve months on and the world has changed in ways no one could have imagined. Gripped by a global pandemic that has shuttered factories, grounded flights and choked demand, the world is awash with energy, and emissions will undoubtedly be down too.

It is hard to comprehend how quickly everything changed as a result of a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, which crossed the species barrier in late 2019 and spread quickly through the Chinese city of Wuhan, the ground zero of the disease now known as Covid-19. At the time of writing in late April, there were at least 3.5 million confirmed cases around the world, more than 250,500 dead and half of the world’s population was under some kind of quarantine or lockdown.

Governments around the world are on a war footing, triggering emergency powers, launching bailout packages for struggling businesses and individuals, and slashing interest rates. As a result, many now fear the impact of a looming deep recession more than they do the virus. At the time of writing, all eyes were on Wuhan to see whether there will be a resurgence of infection as restrictions are lifted in April: this will guide how other countries respond to the virus.

For energy markets, it has been a torrid first quarter: having opened the year at US$65 a barrel, by the end of March, benchmark WTI was trading at US$20.51, a 17-year-low, before falling into negative territory on April 20. The crash was precipitated by the dramatic cut in Chinese oil demand, which fell off a cliff as the world’s second-largest economy brought in unprecedented measures to curb the spread of the virus. In early March, the International Energy Agency, or IEA, forecast a year-on-year fall of 1.8 million barrels per day, or bpd, in Chinese oil demand in the first quarter of 2020, with global demand dropping by 2.5 million bpd for the three-month period. The Paris-based energy watchdog anticipated a recovery over the second half of 2020 as countries successfully contained the virus, muting the global demand drop for the whole year to 90,000 bpd.

The virus moves fast, however. By late March, analysts were scrambling to keep pace with developments. Oslo-based Rystad Energy, for example, which produces weekly Covid-19 reports, released “another shocking consecutive revision” of its weekly estimates as the crisis deepened. At the time of writing in late March, the Oslo-based analyst expected global oil demand, which was 99.9 million bpd in 2019, to fall 4.9 percent in 2020, or by 4.9 million bpd year-on-year, to 95 million bpd.

Return of Single-digit Oil?

The turmoil in the oil markets has been exacerbated by the price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia. The oversupply of oil was expected to balloon when the agreement between the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries’ oil cartel and Russia ended in April, with Riyadh announcing plans to raise oil exports to a record 10.6 million bpd from May in a shock-and-awe tactic to grab market share.

Then, on April 12, OPEC+ – a coalition of OPEC countries and cooperating non-OPEC countries, including Russia – agreed to cut output by 9.7 million bpd in May-June, 7.7 million bpd in July-December, and 5.8 million bpd in January-April 2021.

With the market massively oversupplied, global storage markets are nearing capacity: as of March 20, analysts at Rystad Energy calculated that 76 percent of the world’s oil storage capacity was already full. With supply expected to outstrip oil demand by an average of almost 6 million bpd in 2020, this will result in an accumulated implied storage build of 2 billion barrels this year.

“The current average filling rates indicated by our balances are unsustainable,” said Paola Rodriguez-Masiu, Rystad Energy’s senior oil markets analyst. “At the current storage filling rate, prices are destined to follow the same fate as they did in 1998, when Brent fell to an all-time low of less than US$10 per barrel.”

This was echoed by Jack Allardyce, oil and gas analyst at Cantor Fitzgerald Europe, speaking in late March. “Global storage is likely to hit capacity over the next two to three months,” Allardyce said. “This is likely to be particularly damaging for U.S. crude, with prices in the Permian region potentially hitting single digits.”

Shale producers, most of which budgeted for oil between US$55 per barrel and US$65 per barrel in 2020, are already reining in spending. And it’s not just debt-loaded independents that are curbing activity; even the mighty ExxonMobil has been forced to cut rig counts in the Permian in response to the price rout.

U.S. shale production has been a game-changer in world energy markets, but even slowing output from these vast fields is unlikely to have much impact given the unprecedented demand-side disruption.

“The oil market is massively oversupplied, much more so than in 2014-2016,” said Dmitry Marinchenko, senior director, corporates, EMEA, at Fitch Ratings. “We don’t yet know how much demand will disappear, but it will be very significant. This is a completely unprecedented situation. Even when we have had recessions in the past, the demand for oil has continued to grow albeit at a slower rate – now demand is shrinking and shrinking. The journey to recovery might be pretty long.”

Gas Glut

It’s not just oil markets that are suffering from the coronavirus effect. “Cuts are likely to be across the board, upstream, midstream, gas, LNG,” Marinchenko said. “The pressure will be felt everywhere.”

Natural gas markets, for example, are already “vastly oversupplied.” Gas prices in Europe and Asia have collapsed to record lows and U.S. prices are at a 25-year-low as stockpiles head towards all-time highs.

This weakness will continue for the next two years, making it an uncomfortable ride for those with exposure to this market. LNG markets are particularly under pressure. A number of major projects, such as BP’s Tangguh Train 3 in Indonesia, are suffering virus-related work delays, while Australia’s Woodside has delayed final investment decisions, or FID, for its high-profile Scarborough, Pluto LNG Train 2 and Browse projects. It will not be the only one deciding to hold off on taking FID this year.

“The LNG market was in glut even before the coronavirus crisis and prices were already low,” Marinchenko said. “It may now take several years for the glut to be digested. In the next two years I expect we will see a very limited amount of LNG projects sanctioned.”

Operators are already running a slide rule over their portfolios in a bid to cut costs and conserve cash flows. Some projects, of course, are too big or too strategic to be derailed. Hans Bergers, advisor, integration management office at Mammoet, which has a number of big petrochemicals clients, said “many of these large projects have a long-term horizon, and their owners will be looking beyond shorter-term factors.”

Many other projects, however, particularly on the exploration and production, or E&P, side, may be put on ice until prices recover. E&P budgets are expected to plunge by up to US$100 billion this year, about 17 percent down on 2019 levels, according to Rystad Energy. Cairn Energy, for example, is undertaking an asset-by-asset view of its portfolio and has already reduced and deferred spending that represents an overall 23 percent reduction in capital expenditure for the year. Shell is slashing underlying operating costs by US$3 billion to US$4 billion over the next 12 months, and capex will be cut by about US$5 billion to US$20 billion. Project sanction of Siccar Point Energy’s Cambo development, one of the largest undeveloped fields on the UK Continental Shelf, has been pushed back from the third quarter of 2020 to the second half of 2021.

More projects will be shelved in the coming months. “Very low oil prices will shrink operating cash flows, which means oil majors and national oil companies will have to offset that by cutting capex, and it’s inevitable that they will start postponing projects,” Marinchenko said.

Big offshore construction projects will take a hit. “We had forecast growth in the floating production systems, or FPS, market for 2020 with up to 18 new contract awards. Now we expect only a handful to go ahead, which would take the FPS market to 2015/16 levels,” said Mhairidh Evans, principal analyst in Wood Mackenzie’s upstream supply chain research team. “Our preliminary analysis suggests global upstream capital investment will fall by at least 25 percent in 2020.”

No Slack Left to Cut

Little wonder that 2020 is shaping up to be a grim year for the oilfield services sector. “The industry has not yet fully recovered from the price collapse of 2014-2016, and many oilfield services companies in particular are still operating in survival mode,” Fitch’s Marinchenko said. “This time, however, there’s far less potential to cut costs. I expect we will see some cost deflation, perhaps around 10 percent to 15 percent in the services sector.”

This was echoed by Evans, who cited “major pricing concessions” in the U.S., where some pressure pumpers have reduced prices by as much as 20 percent, while rig rates have dropped by about 15 percent.

Offshore drilling markets are also feeling the squeeze, partly as a result of the crew and logistical challenges of moving personnel and equipment against the backdrop of a global pandemic, and partly because of contracts being canceled.

According to Westwood Energy’s RigLogix service, more than US$1.6 billion in contract value is at stake for options that are due to be exercised this year, with projects in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East making up more than half of the total. With the number of idle rigs on the increase and debt repayments looming in 2021, Terry Childs, head of RigLogix, says many U.S. drillers will be in Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2020 or 2021. He also thinks that “most” of the near 300 drilling programs that currently have 2020 start dates will be delayed.

Rystad Energy adds that more than a million jobs in the oilfield service industry are likely to be cut in 2020, with shale services expected to bear the brunt of the cuts. WoodMac’s Evans is equally gloomy.

“Companies had already cut so much, it’s hard to identify further savings without drastic measures,” Evans said. “This includes refinancing and the restructuring of business models. Headcount cuts and bankruptcies are inevitable.”

Renewables Driving the Recovery

The renewables sector is not immune from the crisis. Lockdown measures that inhibit worker mobility and disrupt supply chains could derail some offshore wind projects in the U.S., China, Spain, France and Italy.

According to analysis by Wood Mackenzie, total forecast wind additions for 2020 is now expected to be 73 gigawatts, down by 4.9 GW as a result of the crisis.

Spanish wind turbine plants LM Wind Power and Siemens Gamesa have been shut, Australia’s strong pipeline of projects relies on 3.6-4.2 megawatt-rated turbines imported from Europe, while auctions in South Africa, Poland, Ukraine and Chile are likely to be delayed as governments wrestle with the pandemic and travel restrictions make it impossible for developers to undertake feasibility studies.

The tougher economic backdrop could also make financing difficult. Renewable projects in Australia, Brazil, Mexico and South Africa will be especially impacted, as projects in the procurement phase could face capital cost increases of up to 36 percent due to the rapid depreciation of local currencies, warned analysts at Rystad Energy.

Even so, the longer-term outlook is positive with WoodMac, noting that there could be a boost for renewables in any post-crisis stimulus package. There is certainly talk of extending tax credits for the renewable energy industry in the U.S., and China is considering relief on its upcoming feed-in-tariff deadline.

“In the months to come, there may be a more concerted effort to weave renewables policies into more sweeping omnibus bills aimed at providing fiscal stimulus in the countries hit hardest by the pandemic,” noted Dan Shreve, head of global wind energy research at WoodMac.

And while in the short term the crisis is likely to stall the oil and gas industry’s carbon mitigation strategies, the longer-term impact could be an acceleration of the energy transition.

Valentina Kretzschmar, vice president of corporate analysis at Wood Mackenzie, points out that at US$35 oil, renewables compete with oil and gas projects – and without the associated price volatility.

“Capital allocation is no longer a one-way street for Big Oil – renewables projects suddenly look as attractive as upstream projects at US$35/barrel,” she said. “In a US$35/barrel oil price environment, investment in renewables represents an opportunity for companies with strong balance sheets, which are in position to think strategically and long term. Diversification into clean energies could ensure their long-term survival.”

Fitch’s Marinchenko backs this assessment. “The energy transition may be impacted in the short term, as for now companies have to prioritize other things because they are in a fight for survival,” he said. “Further out, these very low prices may remind companies that relying on oil and gas production may make their business model more volatile. The green agenda won’t be forgotten, but in the short term they are going to be focused on cutting costs in their traditional business.”

Medium Term Outlook

But the Covid-19 crisis won’t last forever. Scientists are racing to develop a vaccine or effective treatment, while South Korea has shown that an early intervention and extensive testing program is a viable alternative to economy-wrecking lockdowns. Companies may have to go into survival mode for 2020, while also developing strategies for a return to normality, when the world’s hunger for energy is revived.

“It is hard to speculate where the next big oil and gas projects will be while we are in the middle of a ‘black swan event,’ ” said William Hill, executive group vice president of GAC Energy.

He does, however, think some wider trends are a guide to emerging areas of interest. “There’s no doubt that Guyana will be an area of interest for many, with ExxonMobil, the main operator in Guyana, announcing that it has discovered more than 5.5 billion barrels’ worth of oil off the country’s coast,” Hill said, pointing out that by the end of the decade, Guyana’s production is forecast to overtake Venezuela. “Africa and Southeast Asia are also growing markets for offshore work, and we shall probably see more deepwater extraction as subsea processing and production technologies continue to mature.”

Hill is also confident that big offshore wind projects will “go from strength-to-strength.”

“2019 was a record year for renewables, with global wind power capacity growing by almost one-fifth,” he said. “This underlines the importance of service providers adapting to this long-term trend to transition what they offer from oil and gas to more holistic offshore work, spanning wind, tidal and other types of renewable power.”

By 2021, analysts expect the recovery to be underway – the IEA predicts a “sharp rebound.” Audun Martinsen, Rystad’s head of oilfield service research, said that by the second half of 2021, with better market fundamentals and a fading Covid-19, “recruitment is likely to pick up in the shale sector and from 2022 will also kick-off in the offshore sector.”

And those companies that do survive this year could be fitter, leaner and smarter as a result. “Companies holding onto idle assets ‘just in case,’ will quickly think again,” WoodMac’s Kretzschmar said. “The prospect of sub-US$40/barrel oil will force profound change in the sector’s footprint. While there’s short-term pain associated with this, it could ultimately create a more sustainable business for those that survive the downturn.”

Bergers of Mammoet, which recently acquired ALE, said the next 12 months may be more difficult, but the longer-term outlook is positive. “For the next five years, we would expect world population and household income levels to continue to grow, and Mammoet will be there to support our customers in achieving this. For now, the most important thing is that our families, colleagues and customers return home safely, each day.”

The message for 2020? Stay safe and hold on.

Freelance journalist Amy McLellan has been reporting on the highs and lows of the upstream oil and gas and maritime industries for 20 years.

Subscribe to BreakbulkONE and receive more industry stories and updates around impact of COVID-19.