May 07 | 2020

President Bids to Restore Business Confidence

By Simon West

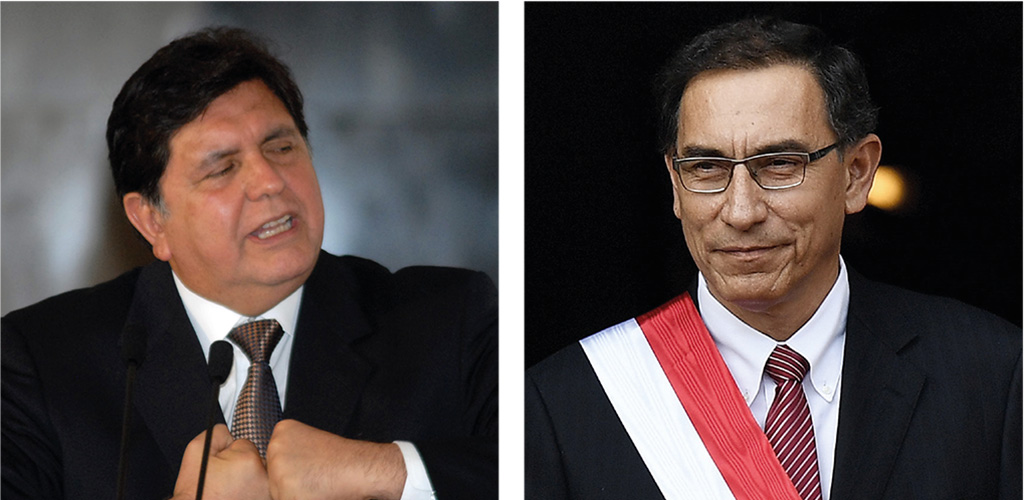

BREAKBULK MAGAZINE ISSUE 3 / 2020 – EMERGING MARKETS – Peru’s former two-time president Alan Garcia was a divisive figure. Just 36 years old when he took office in 1985, the then-leftist leader oversaw a chaotic first five-year term marked by economic crisis and hyperinflation, only to be re-elected for a second term in 2006 on a more right-wing platform.

It was during this second spell in charge that he allegedly began taking kickbacks from disgraced Brazilian constructor Odebrecht in return for lucrative public works contracts, including a new metro system for capital city Lima.

After a lengthy probe, police were sent last April to his home in Lima with a preliminary arrest warrant. But before officers could carry out their orders, Garcia put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger, succumbing to his injuries shortly after.

The ex-leader had maintained his innocence until the end, tweeting just days before his suicide that his accusers had been the real crooks.

“He was a very controversial figure – some people loved him, some people hated him,” said Beatriz De la Vega, energy leader at consultancy firm EY Peru. “In the end he preferred to die rather than being jailed, even though everybody knew he was involved in many corruption cases.”

Garcia’s death was the most shocking turn yet in a continent-wide graft and money-laundering scandal that has blackened the region’s highest echelons of power.

In a 2016 plea deal with the U.S. Justice Department, Odebrecht admitted that for more than a decade it had dished out almost US$800 million in kickbacks to unscrupulous politicians and officials for infrastructure projects in a dozen Latin American and Caribbean countries.

Marcelo Odebrecht, the former head of the conglomerate, was given a 19-year jail sentence in 2016 for his role in the scheme, although that was reduced to house arrest two years later.

Trouble Dents Confidence

According to former Odebrecht executives-turned-whistleblowers, in Peru alone millions of dollars swapped hands, with surviving former presidents Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, Ollanta Humala and Alejandro Toledo, and opposition leader Keiko Fujimori, daughter of jailed ex-president Alberto Fujimori, implicated in the racket.

Several ambitious engineering projects were either abandoned or put on hold, including the Gasoducto Sur Peruano, or GSP, a 1,100-kilometer pipeline network stretching across central and southern Peru. A 30-year concession to build and operate the GSP was awarded in 2014 to a consortium led by Odebrecht, only for the US$7 billion deal to be scrapped three years later after key financing deadlines were missed.

The GSP would have provided abundant natural gas feedstock for several proposed petrochemical plants in southern Peru. Those projects, like the GSP, have been shelved.

The participation of so many high-profile public figures in the scandal has driven home the scale of corruption in Peru, which according to government estimates costs the economy US$10 million every day.

“Since what happened with Odebrecht, people are even more concerned about this issue,” De la Vega said.

In a bid to restore business confidence and salvage the public’s trust in democratic institutions, the country’s new president, Martin Vizcarra, has made tackling graft a centerpiece of his administration.

A tall order perhaps, but the 57-year-old former vice president, who took charge in March 2018 after Kuczynski was forced to resign amid his financial ties to Odebrecht, is making good on his promise and winning popular support for his reforms.

A crucial victory came in December 2018 after Peruvians overwhelmingly backed an anti-corruption referendum that addressed the re-election of lawmakers, financing of political parties and the appointment of judges.

Infrastructure Drive Kickstarted

“Today Peru won,” Vizcarra tweeted shortly after the result. “We have a lot of work to do to bring well-being to all Peruvians. The task is massive, but we have the strength and commitment of everybody to put Peru first.”

Then, in a move that could directly benefit project cargo, late last year Vizcarra approved new measures aimed at reducing bureaucracy and speeding up the government’s five-year national infrastructure plan for competitiveness, or PNIC, launched in September.

The PNIC, designed to reinvigorate the economy and plug Peru’s infrastructure gap, calls for the completion of 52 high-priority projects worth some 100 billion Peruvian soles (about US$29 billion) in the transport and communications, agriculture, sanitation and energy sectors.

The plan will see upgrades at the country’s largest port, Callao, located on the outskirts of Lima, a second and third line for Lima’s metro system and an expansion of the capital’s Jorge Chavez International Airport.

Many of the projects will require project cargo support, such as the completion of the San Gaban III hydroelectric plant in southern Puno department, the upgrade and modernization of the Huancayo-Huancavelica railway and the construction of SITGAS, the pipeline project slated to replace the shelved GSP.

A fresh bidding process for SITGAS is expected to be launched this year.

More than half of the PNIC projects will be built under a public-private partnership model, with the remainder state-funded, according to a government filing. Construction at 24 of the 52 projects has already begun, with work at another 25 close to starting. The remaining three projects are still in the design phase.

“This is not a list of good intentions,” said Vizcarra at the launch of the PNIC. “There is certainty and conviction that they will be completed. By 2025, 95 percent of the projects included in the PNIC will be finished. We are not talking long term.”

Overcoming Red Tape

In a bid to overcome the bureaucratic obstacles that hamper infrastructure projects in Peru – which, in turn, often spur acts of corruption or fraud – the government published in November an emergency decree listing more than a dozen measures designed to reduce red tape and improve supervision.

“One of the most important measures deals with the freeing up of land,” said Yulia Valdivia, analyst at the Peruvian Economy Institute, or IPE. “For example, the comptroller general’s office warned last year that this was the main cause of delays in the expansion of the Jorge Chavez International Airport.”

The US$1.5 billion project has been repeatedly delayed because of disputes over the government’s delivery of land required for the expansion. The new measures would help bypass this problem by allowing owners of the projects listed in the PNIC to have a more direct role in dealing with interference.

The decree, valid for three years, could help lure much-needed investment to Peru’s crumbling infrastructure network, although for many in the private sector, decades of rampant corruption have left their mark.

“The opportunities (in the PNIC) are there, but government corruption slows everything down. Many projects that get awarded are overvalued, and then are never finished or are left half-done,” said Jhonn Trujillo, manager at Lima-based Trust Cargo Consulting.

Renatto Castro, project manager at Andina Freight, a breakbulk specialist that has worked on some of Peru’s largest industrial projects including last year’s expansion of Southern Copper’s Toquepala mine in southern Tacna department, said curbing corruption is vital for boosting infrastructure spending.

“There is little investment in ports and airports that would allow us to receive high-tonnage equipment more quickly. Although the roads are reasonable, they are not up to international standards, so those involved in logistics face greater challenges when organizing transport and operations throughout the country, especially when it comes to oversized or overweight cargoes.”

Port Limitations Remain

Of Peru’s five main ports, only the heavily congested Callao with its five docks boasts the infrastructure for large-scale projects, although an ongoing modernization project at Salaverry on the northern coast is expected to ease traffic.

“If we have to receive project cargo in other ports, and the ships are gearless or do not have special drafts, we are going to have problems allocating resources, which obviously increases costs,” Castro said. “Clearly there is much to do in port infrastructure, loading equipment and road upgrades. Projects continue to rise, but installed capacity remains the same.”

Vizcarra will be banking on his anti-corruption crusade to restore some investor confidence, but with no political party of his own, further success will hinge on securing parliamentary support.

The president controversially dissolved Peru’s Congress last September after a long-running standoff with Keiko Fujimori’s hard-line Popular Force party, which had repeatedly blocked his reforms.

The move, dubbed a “coup” by opposition members, but deemed constitutionally legal by the country’s top court, was backed by the public, the police and armed forces.

Vizcarra received a welcome boost in January after Popular Force lost dozens of seats in fresh congressional elections. Fujimori herself is serving a 15-month pre-trial prison sentence amid an ongoing probe into her alleged Odebrecht dealings a decade ago.

“Although fragmented and comprised of an unusual and unpredictable group of parties, this parliament will still likely get behind President Martin Vizcarra’s anti-corruption drive,” U.S.-based security analysis firm Stratfor said in a recent report.

“And the main force blocking that drive for two years – Popular Force – now has much less parliamentary clout. This result could mean the passage of promised anti-corruption legislation, see the country’s Senate reconvene, end parliamentary immunity and produce significant reforms to Peru’s arcane campaign finance system.”

Still, with presidential and congressional elections scheduled for 2021, the new parliament will be short-lived. Vizcarra is constitutionally barred from running for president again, meaning he has little time to push through his reforms.

Stratfor warned that a new government in 2021 could take Peru in a different direction. And as the Covid-19 pandemic unfolds, Vizcarra will have even less time to achieve his goals.

Colombia-based Simon West is a freelance journalist specializing in energy and biofuels news and market movements in the Americas.