Dec 15 | 2020

Lessons learned inform future solutions

By Gary Burrows

From navigating through a tsunami to delivering oversized cargoes through the most treacherous of environmental issues, once-in-a-lifetime project moves become bedrock foundations for industry best practices.

Breakbulk Veterans kicked off Dec. 9 with a webinar of leaders with decades of experience, offering examples of complex and lessons learned that have been applied in their careers and provide timely advice for today’s projects.

Bringing together a vast wealth of industry experience, Breakbulk has curated an opportunity for industry veterans to share their experiences and problem-solving skills in a new forum.

The webinar was moderated by Breakbulk Veterans’ Chairman John Amos, former head of global logistics for Bechtel Corp. and now president of Amos Logistics.

Amos has been in the industry for more than 45 years and noted that one webinar attendee had “accused me of handling logistics on Noah’s ark.” He has been instrumental in Breakbulk Events & Media’s development over the years, including serving as a member of Breakbulk’s media advisory board.

Following are summaries of webinar panelists, and their lessons learned.

Murray Cooper, director corporate governance, LV Group

Murray Cooper, director corporate governance, LV Group[Presentation for download]

Based in Singapore, Cooper has been in the industry for more than 35 years involving in mining, oil and gas, industrial projects, resources and renewable energy in Australia and Indonesia, as a shipper and project logistics provider. He is also a member of Breakbulk’s media advisory board.

Project: Cooper worked for a company that shipped millions of dollars of subsea fiber-optic cable and was preparing for two shipments from the loadout port of Hitachi in Japan to Dubai. While the

first shipment of 72 kilometers of cable went well, on March 11, 2011, a tsunami struck Japan, wiping out the Fukushima nuclear power station, and striking Hitachi Port, near the tsunami’s epicenter, with a 130-foot wave.

first shipment of 72 kilometers of cable went well, on March 11, 2011, a tsunami struck Japan, wiping out the Fukushima nuclear power station, and striking Hitachi Port, near the tsunami’s epicenter, with a 130-foot wave.Radiation from the power station was a risk, and all personnel in the vicinity of the tsunami were evacuated. The port was closed to shipping as debris polluted the shoreline. The shipping lines declared force majeure and the vessel charter owner refused to present the vessel. Cable production, near the port, was halted and the lead-time for alternate sourcing would have taken about a year.

“The extent of the devastation was incomprehensible,” Cooper said. With the potential of litigation and loss of reputation, “it was serious trouble. Then the inevitable call from the project director came: ‘Let’s get this done Murray, it’s your problem.’ ”

In attacking a solution, Cooper applied a five-step process referred to as “CHAOS:”

- Communication, to ensure compliance and certificates are in place.

- Hazard identification studies, to identify issues, “and there were plenty.”

- Action Items, including risk assessment.

- Options and Opportunities.

- Support services – with the service provider and stakeholders involved to assure alignment.

“We were there in the planning phase and spent 10 days working through the loadout plan with the Japanese supplier and all the stakeholders involved – stevedores, port authority, ship agent, etc.,” he said. That effort was somewhat complicated by the fact that people on his team in Japan were injured or had lost family from the catastrophe and weren’t immediately available. However, after some chaotic days, he was able to restore and locate people from nearby areas.

The plan shifted to using a tug-and-barge, and a local operator was employed. Cooper’s team negotiated a revised charter party agreement for the “mother vessel,” and alternative octagonal tanks were loaded with the cable and sealed, then loaded onto the barge where they were lashed and ready for transport from Hitachi to Osaka. There it was transshipped onto the mother vessel “and everything went to plan from there,” he said.

Lessons Learned: “It is important to get to the site of the action and pay attention to detail,” Cooper said. “Supply chain disruptions can be fatal if there is no contingency plan in place. But the lessons learned from the past are helping us combat the supply chain disruptions we’re experiencing today.”

Edward W. DeFrancescom president, Universal LandSea Transport Inc.

Edward W. DeFrancescom president, Universal LandSea Transport Inc.

[Presentation for download]

Based in New Jersey, DeFrancesco has been in the industry nearly 50 years, starting in liner and moving into chartering and heavy-lift. As agents for Jumbo in the U.S. he has been “over the mountains and through the hills with many, many projects.

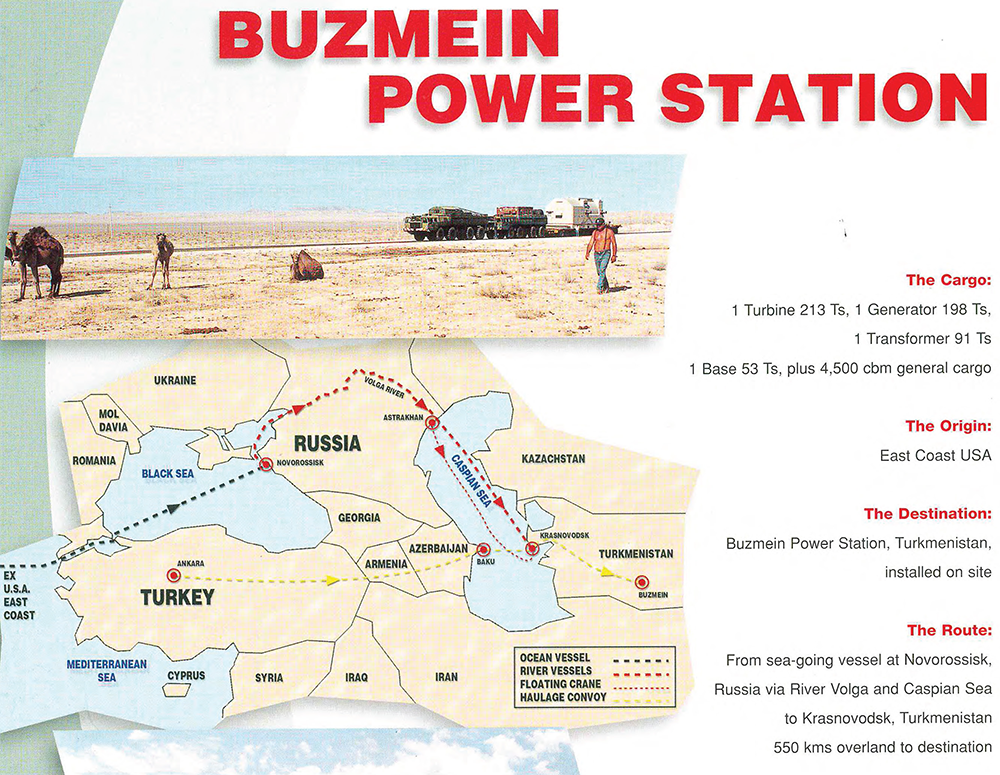

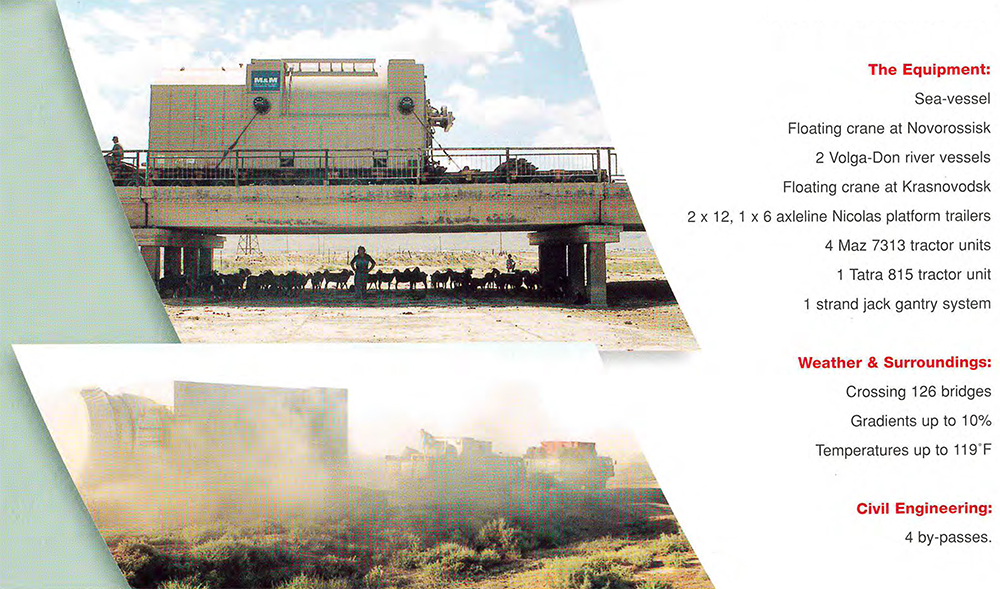

Project: Jumbo in 1996 was contracted to deliver abnormal-sized power gen components from the U.S. East Coast to a remote site in Büzmeyin, Turkmenistan. Following a 25-day ocean segment to the seaport of Novorossisk, Russia, the components were discharged into two non-geared “Volga-type” vessels, for passage into the Caspian Sea to the port of Krasnovodsk. Jumbo arranged for a heavy-lift floating crane to be brought in to meet the Volga vessels, where the components were discharged onto two 12-axle platform trailers and four Russian transport carriers for the 550-kilometer convoy from Krasnovodsk to the Büzmeyin site. The route included 10 percent gradients through the mountains, creation of four desert bypasses and crossing 126 bridges, all in temperatures reaching 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

DeFrancesco’s team assessed every bridge to determine that if they could support the heavy convoy.

Planning and surveys took about two months. Dealing with local authorities – stevedores, export/import licenses with unfamiliar standards – as well as the rough, undeveloped sites required unique solutions, he explained.

Planning and surveys took about two months. Dealing with local authorities – stevedores, export/import licenses with unfamiliar standards – as well as the rough, undeveloped sites required unique solutions, he explained.“That the equipment was safely delivered, on schedule, in those conditions we believed was quite an achievement.

Lessons Learned: Don’t take for granted that the way you operated in other areas will work everywhere. “Pay close, close attention to local conditions and procedures,” he concluded.

Philippe Somers, co-founder and CEO, ACE 54

Philippe Somers, co-founder and CEO, ACE 54Somers was a 30-year industry veteran before founding ACE 54 in Dubai, which caters to mid-sized and niche international project forwarders. He recently returned to his native Antwerp, Belgium to set up a European office. In his career, he worked on five different continents for Danzas, DHL, Geodis and deugro, as well as ACE 54.

Topic: How contracts and terms and conditions (or T&Cs) have become more demanding and difficult, and how the landscape has changed for global project forwarders.

“Global project forwarders have drawn the industrial project industry to a matrix system, and that has created opportunities for international niche players,” Somers said. Clients are looking at “one liability, one international project forwarder with global representation.”

However, while global forwarders have offices in many global markets, those satellite offices are not necessarily equipped with project expertise, he said, adding that he’s particularly witnessed this in Africa. Asset owners and the international project forwarders face complexities with local terms and conditions, including local content requirements, and currencies.

He noted an example of a pipeline project from Nigeria to Ghana, through Benin and Togo. His company worked with a local heavy-lift company, a local specialist in customs brokerage and hands-on experience. The “local heroes” relied on support from the international companies that shared engineering and other expertise as well as setting quality, health, safety and environmental processes.

Lessons Learned: The project industry will increasingly rely on a combination of international intelligence coupled with local expertise to orchestrate safe, effective execution and mitigate risk.

Riccardo Tippmann, former director and board member of Fagioli Group, and now a consultant with RTC

Riccardo Tippmann, former director and board member of Fagioli Group, and now a consultant with RTC

Based in Milan, Italy, Tippmann is a 41-year industry veteran and joined Fagioli in 1985, serving on heavy-lift projects employing sea, air and heavy transport.

Project: A full refinery move for Pemex in Tula, Mexico, on the Mexican Plateau, involving a half-million tonnes of cargo from all over the world, including four hydrocracking reactors from Japan, weighing 1,200 tonnes each.

Fagioli had only a few months to define method of transport and present the client with a solution, including how to break the reactors down into moveable modules, which had to be brought from Veracruz port up 2,100 meters to the plateau. Tippman and his task force reviewed all aspects of the itinerary, including permitting requirements and discussion with authorities, as the route would snake through many little villages. Efforts included building wooden models to test transit passages.

Fagioli leased area within the port to stage the shipments, including the reactors which were broken down into 400-tonne modules. Sixteen convoys hauling up to 650 tonnes each moved the 400- to 500-kilometer route, with sections delivered in proper sequence for them to be assembled. The refinery was delivered successfully.

Lesson Learned: Plan as much as possible in advance to avoid having to “invent solutions” for challenges during a move.

“I’m not saying the rest was easy, but the execution was possible” due to the advanced planning, Tippmann said.

Breakbulk Veteran Murray Cooper worked for a company that shipped millions of dollars of subsea fiber-optic cable and was preparing for two shipments from the loadout port of Hitachi in Japan to Dubai. While the first shipment of 72 kilometers of cable went well, on March 11, 2011, a tsunami struck Japan, wiping out the Fukushima nuclear power station, and striking Hitachi Port, near the tsunami’s epicenter, with a 130-foot wave. Here’s how he saved the transport.

Subscribe to BreakbulkONE and receive more industry stories and updates around impact of COVID-19.

.png?ext=.png)

_1.jpg?ext=.jpg)