Sep 27 | 2021

US$12 Billion-a-Year Bounty Beckons off US Coastlines

By Paul Scott Abbott

By Paul Scott AbbottPropelled by the Biden administration’s aggressive climate-change-fighting goals, winds off U.S. shores offer a US$12 billion-a-year bounty for clean energy industry players and supply chain providers.

The impressive annual investment figure, plus an estimate of 80,000 jobs to be created, highlight efforts to responsibly pursue renewable energy development along the Outer Continental Shelf.

Meeting the goal of deploying 30 gigawatts, or GW, of offshore wind energy production by 2030, as set forth by Joe Biden shortly after assuming the nation’s presidency in January, “will trigger more than US$12 billion a year of investment off our coast, and it’s beginning now,” said Walter Cruickshank, deputy director of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management in the U.S. Department of Interior.

“There is tremendous potential for offshore wind here in the U.S.,” said BOEM’s Cruickshank, who holds a doctoral degree in mineral economics from Penn State and has worked in the Interior Department for more than 35 years. “There’s a lot of opportunity to invest in both the wind farms themselves and the supply chain.”

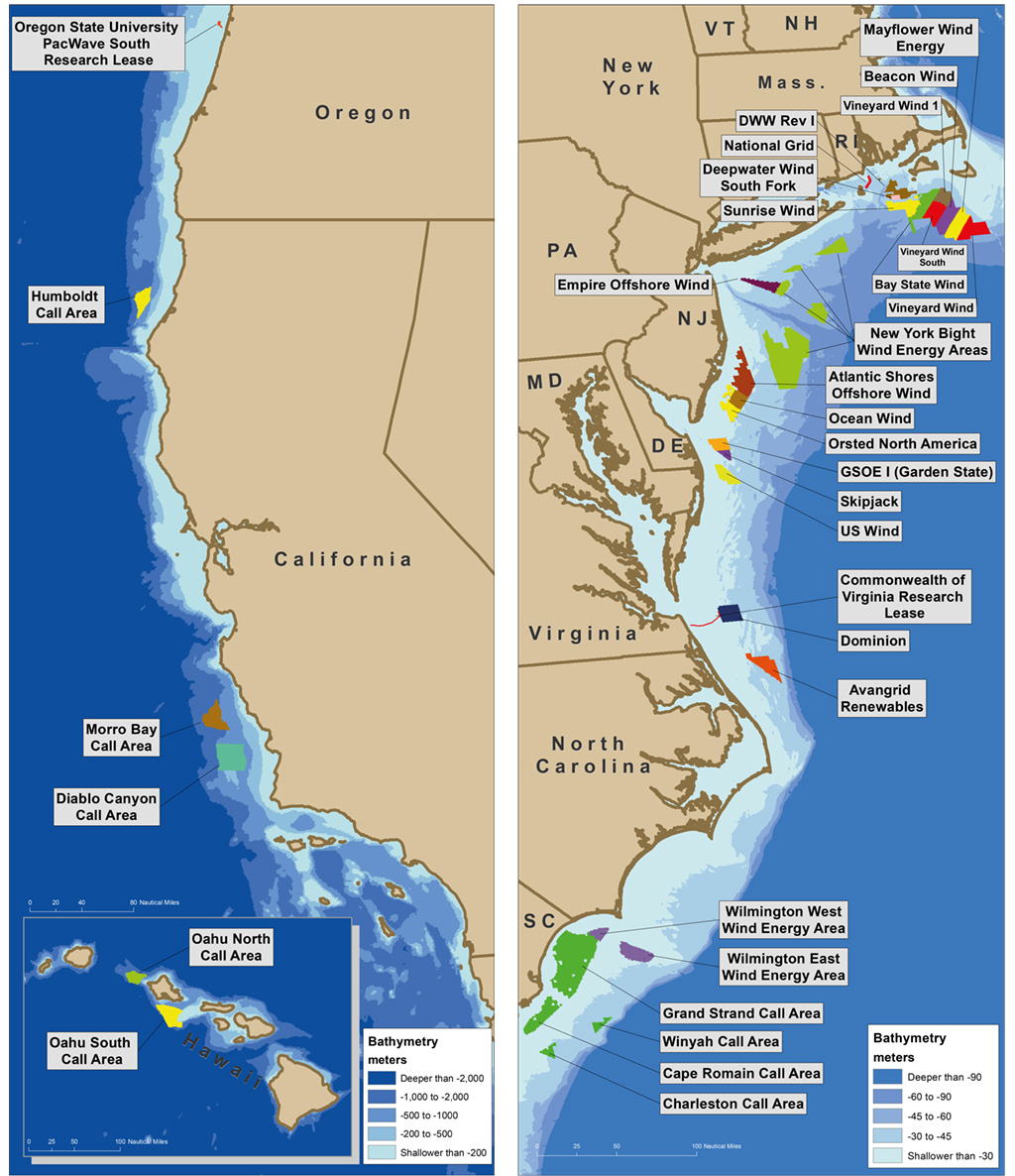

While present activity is focused off Atlantic and, to a lesser extent, Pacific coastlines, the Gulf of Mexico proffers significant potential as well, thanks in large part to the extensive oil and gas industry infrastructure already in place, according to Cruickshank and other observers.

Cruickshank’s optimistic views are supported by project cargo supply chain providers and by the chief executive of the not-for-profit group dedicated to building the U.S. offshore wind supply chain, as expressed in separate interviews with Breakbulk.

‘Exciting Time’

“This is an exciting time for the U.S. offshore wind industry,” said Liz Burdock, CEO of the Towson, Maryland-based Business Network for Offshore Wind. “There is tremendous domestic opportunity for project carriers and freight forwarders looking to join the offshore wind industry, in part due to the uniqueness of offshore wind project development and the U.S. market.”

Burdock cited the sheer size of offshore wind project components – with 900-foot-tall towers, blades as long as 400 feet and nacelles weighing as much as 600 tonnes – which make them very difficult to transport by land and which will require development of new quayside staging and manufacturing facilities.

“The U.S. has massive offshore wind resource potential,” Burdock said. However, three principal challenges must be addressed if the nation is to reach its goals.

“First,” she said, “to meet the combined state and federal goals, the country must develop a robust domestic offshore wind supply chain. This is a once-in-a-generation opportunity for entrepreneurs to get into a growing market and for existing businesses – be it maritime, engineers, welders, aviation, O&G [integrated oil and gas] and so on – to diversify.”

A second hurdle, already earmarked for federal funding, deals with upgrading the nation’s onshore electricity grid infrastructure so new power sources can efficiently and effectively power homes and businesses.

Third, Burdock said, depths off much of the U.S. coastline are too substantial to accommodate fixed-bottom installations, thus requiring floating turbine technology, which, she said, “can become a great strength if the U.S. embraces it as an opportunity to be a global leader in floating wind research and development.”

Furthermore, according to Burdock, state-driven procurement processes often designate desired ports for marshalling, assembly and installation activities, and Jones Act requirements, demanding use of U.S.-flag vessels, add more layers to an already complex logistical puzzle.

“For project carriers and freight forwarders,” she said, “that means opportunities abound, and innovation is needed.”

Gulf has Leg Up

One way in which the nascent offshore wind market may take advantage of existing capabilities is in utilizing the vast infrastructure supporting the more traditional oil and gas industry along and in the Gulf of Mexico.

“There is a great deal of offshore energy in the Gulf of Mexico,” said BOEM’s Cruickshank, positing that oil and gas vessels have potential to be repurposed and/or retrofitted to serve the wind market. “Offshore wind can take advantage of the infrastructure that’s there.”

Cruickshank noted that the foundation for the first U.S. offshore wind installation – the 30-megawatt-capacity Block Island Wind Farm opened off Rhode Island in 2016 – was built at Gulf Island Fabrication in Houma, Louisiana.

In addition, the nation’s first Jones Act wind turbine installation vessel, or WTIV, is being constructed at the Keppel AmFELS shipyard in Brownsville, Texas, at a cost of US$500 million, using 14,000 tons of domestic steel and providing 700 jobs.

The 472-foot-long WTIV, on target for late 2023 delivery, is being built for Richmond, Virginia-headquartered Dominion Energy, which plans to base the vessel out of Hampton Roads, with a U.S. crew, in support of installation of more than 5 GW of wind generation capability off the Atlantic Coast.

Nonetheless, the Gulf of Mexico only recently has been eyed by BOEM for potential offshore wind installations, with the Department of Interior agency publishing a June 11 request for interest in future development off the shores of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland called the request “an important first step to see what role the Gulf may play in this exciting frontier.”

A pair of February 2020 studies by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, funded by BOEM, found the shallow, warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico to be highly suitable for offshore wind energy development. The studies pointed to advantages related to the existing offshore oil and gas infrastructure, but also cited technological challenges posed by hurricane exposure, lower wind speeds and softer soils.

Endeavors Proceed

Meanwhile, most of the significant recent BOEM activity has related to the U.S. Atlantic Coast, involving endeavors from New England to the Carolinas, plus a pair of July actions dealing with California – the first a call for information to determine industry interest in development within the 399-square-mile Morro Bay areas off Central California, and the second being advancement to the environmental review stage for the 206.8-square-mile Humboldt Wind Energy Area off Northern California. California has a goal of producing all of its electricity from carbon-free sources by 2045.

Perhaps most notably off the U.S. East Coast, the Biden administration in May approved construction and operation of the Vineyard Wind I project as the nation’s first large-scale offshore wind undertaking. About 12 nautical miles off the Massachusetts islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, the approved project calls for installation of as many as 84 turbines as part of an 800-megawatt, or MW, facility aimed at powering 400,000 homes and businesses. In June, BOEM began an environmental review of the Vineyard Wind South project, which calls for phased development of a 2 to 2.3-GW facility farther off the shore of Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

June also saw BOEM proposing the first competitive offshore wind lease sale under the Biden administration – for the New York Bight area of shallow waters between Long Island and the New Jersey Coast – with potential to unlock more than 7 GW of clean energy.

Then, in July, BOEM announced its intention to conduct an environmental review of a proposed 69-turbine wind energy project off the shore of North Carolina, which has set goals of developing 2.8 GW of energy off its coast by 2030 and reaching 8 GW (enough to power 2.3 million homes) by 2040.

As of late July, according to Cruickshank, the U.S. government had issued 18 commercial leases for wind farms in the Atlantic, with plans for additional lease sales in the near future.

Also in July, Denmark-based Ørsted, owner and operator of the pioneering Block Island installation, announced the submission of a bid to develop the 760-MW Skipjack Wind 2 project off the Maryland shore.

Providers Gear Up

With all of this immediate activity and the Business Network for Offshore Wind’s Burdock calling President Biden’s goal for 2030 “just the tip of the iceberg in terms of projects the U.S. can anticipate in the coming years,” it is little wonder that project supply chain providers from New Jersey-based Blue Water Shipping to a unit of Danish shipping conglomerate Maersk are gearing up to meet demand.

“The hottest thing around today is the offshore wind in the United States,” said Brent Patterson, Blue Water Shipping’s regional director of Americas energy and projects. “The vision here over the next 10 years is to deploy the offshore wind expertise we have developed in Europe over the past 30 years.”

“The hottest thing around today is the offshore wind in the United States,” said Brent Patterson, Blue Water Shipping’s regional director of Americas energy and projects. “The vision here over the next 10 years is to deploy the offshore wind expertise we have developed in Europe over the past 30 years.”As Blue Water Shipping looks to significantly expand its presence in the U.S. offshore wind energy arena, the company in July brought aboard a new head of renewables with extensive experience in the sector while opening a pair of offices in New England.

Blue Water Shipping’s new hire is John O’Keeffe, most recently head of marine affairs for North America for Ørsted, the world’s largest developer of offshore wind power. O’Keeffe led Deepwater Wind – now part of Ørsted – in development of the Block Island Wind Farm.

“This is a unique opportunity for us at Blue Water Shipping,” Patterson said, noting that Blue Water provided marine logistical support for the Block Island project among more than 30 global offshore wind projects with which the firm has been engaged.

While O’Keeffe’s responsibilities will also include such areas as solar energy and hydro-renewables, he is expected to devote much of his efforts to offshore wind, for which Blue Water Shipping furnishes turnkey management from receipt of the oversize components, to laydown and storage management, to loadout for transport to offshore installations.

To best serve the offshore wind market that is emerging in particular in waters off the U.S. Northeast, Blue Water Shipping this year opened new offices in Boston and in Providence, Rhode Island.

Floating Future

Maersk Supply Service’s director of floating wind solutions, Aberdeen, Scotland-based Yvan Leyni, said he sees floating offshore wind farms – as opposed to bottom-fixed installations – offering the greatest potential in the U.S. and elsewhere, with waters off the U.S. Northeast holding much promise.

The Maersk unit, which is partnering in a small-scale demonstration project targeted to be ready by 2023 off the Maine coast, has been engaged in offshore wind projects in Europe and Asia for 15 years, Leyni said.

“Floating wind is one of the key elements in our strategy now,” Leyni said, adding that about 80 percent of oil and gas expertise is transferable to offshore wind, including in providing broad-spectrum engineering, procurement and construction and engineering, procurement, construction and installation services that may well encompass laying cables between turbine units and for exportation of power to the shore. “We are using our experience from oil and gas. It’s very transferable to floating wind.”

Leyni said floating wind offers several advantages over bottom-fixed installations, including better wind quality farther from the coastline and the aesthetic benefits associated with being a greater distance from shoreline view.

The Biden administration commitment, he said, should help speed approval and permitting processes and also furnish some project funding assistance. Currently, according to Leyni, the cost for a single turbine for a demonstration project can run as high as US$50 million.

“Over the next four to five years, you’re going to start to see the real big commercial wind farms,” Leyni said.

Through the end of the 2020s, he said, numerous commercial projects are anticipated to come online off the coast of the U.S. Northeast, with California offshore wind undertakings to be producing power late in this decade, to be joined after 2030 by projects off Hawaii. As for when commercial wind projects are likely to be seen in the Gulf, Leyni predicted, “not in the next eight to 10 years – nothing before 2030.”

A professional journalist for more than 50 years, U.S.-based Paul Scott Abbott has focused on transportation topics since the late 1980s.

Image credit: Maersk Supply Service