Mar 21 | 2023

Commercial Invoice and the Country of Origin

.png)

We have spent a few articles getting to understand a Commercial Invoice (CI), its underlying data and the knowledge necessary to submit correct export and import information to facilitate international movements. We have looked at the layout of the CI, the data for the Customs Authority to calculate the applicable duties for imports, and the license to allow the goods to move out of a country. The last piece of the CI conundrum is the Country of Origin (COO), which we will explore in this article and use it to summarize and wrap up the CI concepts.

The CI is the one document which the exporter creates, or provides the data for, and submits to the exporting and importing country’s Customs Authority. The submission explicitly states that the data is correct; failure to provide accurate and precise information is essentially fraud, and the penalties can be severe if the Customs Authority chooses to prosecute. Even without prosecution, imagine a Customs Authority that stops all exports while it reviews all your submissions for the last few years. You can only appeal to the Customs Authority to allow the goods to be exported, and the only legal route is through a Customs Court. Not a situation you want to be faced with.

The COO is fraught with problems. What a way to start a discussion. The World Customs Organization (WCO) acknowledges that there should be simpler ways to define the country of origin for all countries, and that the WCO should publish them in the future. The problem is in the absence of a universal way to decide the country of origin, most of the Free Trade Agreements (FTA) in place today have their own rules. The plethora of FTA means the waters are now really murky with each one introducing what the negotiators (not necessarily trade experts) wanted to include and moving further from a simple universal set of rules. The only way to decide on the correct COO is to refer to the FTA between the two countries and apply those. The fact that these highly complex rules for a COO must be deciphered for a product means this is a job for a highly focused and experienced trade specialist.

There are some principles which are used in most of the FTA rules for the COO. These are summarized as follows. The first is where the goods are altered from their current HS (Harmonized Schedule of Tariffs or HTS) classification to a new and different classification. For example, a number of items which are assembled and made into a new usable product. The usable product is then a different HS classification and it is deemed to be made in the country where this transformation took place. Please note the principle of transformation, as merely adding a discrete item and repackaging it is not a transformation. The classic is a toy with batteries added, which in this case the toy is not transformed, and the toy COO and the batteries COO must remain for each item. The more complex example would be, say, a gearbox where a housing, bearings, and the gears are sourced from multiple countries. The assembled gearbox is a different HS classification and is deemed to be made in the country of assembly.

Where the Transformation Rule is not applicable, the rule is generally where the largest value of the goods is sourced. The goods can be sourced from different countries, and the calculation of the value of the goods from each country is then made and the dominant country is the COO. The definition of the value of the goods can be based on the total cost, or the net cost, depending on the countries involved and the agreements between them.

The true COO is determined using the appropriate rules for the trade between the two countries. Now comes the part where you need to store the goods awaiting shipping in your warehouse. If the goods are always sourced from the same country and manufacturer there is one storage location only. But what happens when these goods are sourced from different manufacturing facilities in different countries? For your company to correctly define the COO, these goods from different countries must be stored separately, so that when they are picked the correct COO is recorded and then added to the CI. Not simple, because the storage location is for an item, but must be sub-divided into different countries. That means an enormous increase in computer data, and the need to ensure the person picking collects the appropriate item from the correct storage sub-division, even though the items are the same in shape and size, increasing the complexity even further. The warehouse must be able to accommodate these issues and deliver the right product and information to generate the correct COO in the CI.

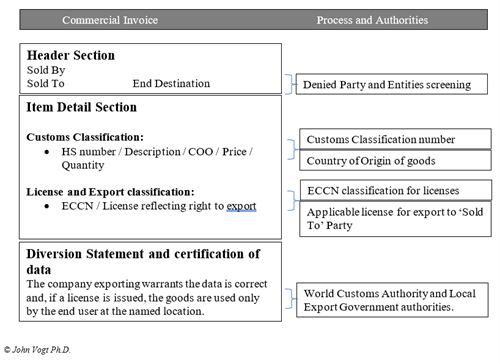

Let’s summarize all this in a simple diagram for a Commercial Invoice:

This shows all the major issues for a CI, and the authorities involved. When depicted like this, it becomes clear the CI is not a simple document. Add to this that when a license is required, the exporting country will demand a ‘No Diversion’ statement your company must sign, this is a complex and demanding document. The ‘No Diversion’ statement explicitly states that your company has ascertained the goods will be utilized by the buyer at the end destination, and will not be resold or traded to third parties. This means the recipient must be a reputable company verified by your company.

And with this, we will turn our attention away from the CI and to the Free Trade Agreements and Free Trade Zones in future articles.

About the Author

John has his own consulting company and, at the end of his 42 years in industry around the world, was the Vice President of Global Logistics for Halliburton. Thereafter he spent five years as a Professor of Record for the University of Houston-Downtown MBA for International and Supply Chain courses. He has experience as a Board Director and has traveled the world to improve trade.

In his career, he has driven the correct use of Incoterms as part of the trade improvements he has implemented to drive efficiency and effectiveness. In his role as a professor of record, he taught multiple courses on the use of Incoterms and trade-related agreements. Alongside his colleague Dr. Jonathan Davis (Associate Professor, Supply Chain Management Chair GMSC Department, Marilyn Davies College of Business, University of Houston-Downtown), he has published three formal research papers on Incoterms with two more in consideration, making him the most published Incoterms researcher. He has also published numerous articles, presented papers at multiple international conferences around the world on logistics, trade and compliance including Incoterms. He has served as track chair for multiple conferences as well.

John has a Ph.D. (Logistics), an MBA, and a B.Sc. (Engineering), holds the title of European Engineer (Eur. Ing), is a Chartered Engineer (UK) and has been elected as a Fellow of the Institute of Engineering and Technology (UK). You can reach John at [email protected].