John Vogt on How to Create a More Resilient Logistics Chain

_7.png) John Vogt, former Halliburton vice president of global logistics and a visiting professor at the University of Houston-Downtown, presents the latest in his long-running series on Incoterms, the internationally recognized set of trade rules that sellers and buyers must follow when devising a contract for the shipment of goods. This week, John looks at the four major elements of risk – operations, tech, natural and socio-political – and their major causes.

John Vogt, former Halliburton vice president of global logistics and a visiting professor at the University of Houston-Downtown, presents the latest in his long-running series on Incoterms, the internationally recognized set of trade rules that sellers and buyers must follow when devising a contract for the shipment of goods. This week, John looks at the four major elements of risk – operations, tech, natural and socio-political – and their major causes.

New installments are published each month on the Breakbulk news page and in our online BreakbulkONE newsletter.

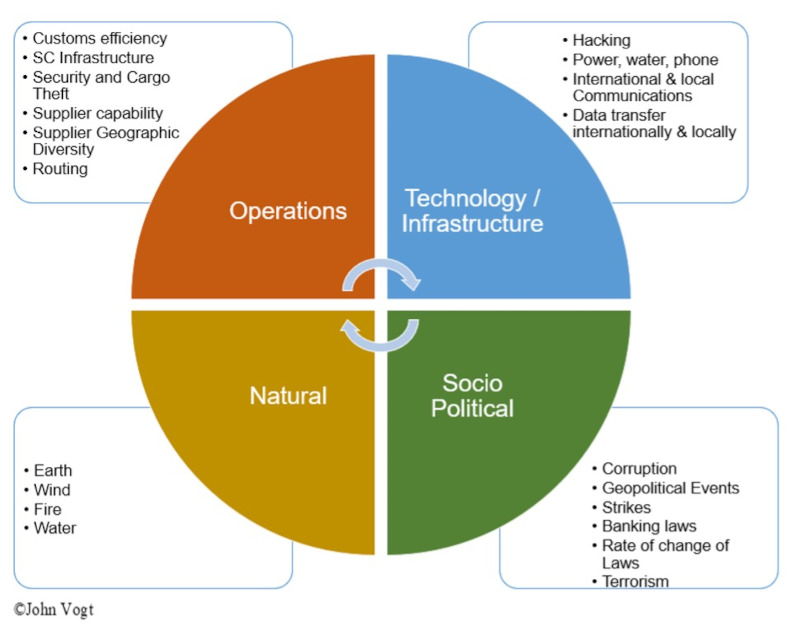

In previous articles here and here we looked at risk and its components. We concluded that resilience could be improved if we recognized risks and planned for them. This planning can be in two major forms. The first is providing alternatives, such as having multiple sources of supply or transport, rather than being dependent on one provider. The second is that knowledge of the risk allows preparation so that plans can be put in place to overcome an issue, minimizing the impact and, thereby, reducing risk and improving the resilience of the logistics chain. We will amplify this resilience in later articles; for now, we want to conclude risk and add a more practical aspect of the theory. We can summarize the four major elements of risk and the major causes in a diagram.

Risk Elements and Synthesis

The risks that need to be considered depend on the industry and location as well as the sophistication of the company. However, as an overview, Figure 1 shows the main categories and issues that must be addressed. Of course, there may be many additional issues that affect a company, and these must be added to this diagram to be comprehensive.

Figure 1: Risk Categories and elements

The consideration of risk in these four categories with multiple aspects in each will ensure that a strategic process considers and includes all the necessary risks. These do not necessarily cover every risk; they are suggestions to evoke the review and thoughts of potential risk. Beware the management that glosses over these and focuses on only a limited number of risks without a wide view. A risk will emerge and cause havoc if it is not planned for and at least understood.

The design of a logistics chain can consciously be made to be resilient. Resilient in this context means able to withstand external changes and forces better than many or all alternatives. In principle this is minimizing the effect of risks on the logistics chain.

Technology has also impacted logistics. Today the modern logistics organization has to use computerized track and trace systems, booking systems, TMS and so on. Hacking in its broadest definition is feasible for these systems. The data for these systems is generally provided by users from around the world and may, or may not, be security conscious. In many cases this human element is the simplest way to access and amend data and or access company information of what is being shipped and the cost prices, for example, shown on customs invoices. These are risks that must be considered, and with the human element involved, this overcomes technological firewalls. The new technology of blockchain has inherent data security, but it is computing power intensive and with the massive amounts of data required for a logistics company it is still to be proven. More importantly, higher security has little value when all the data is entered by people, and the human element can and will override any systems integrity and security such as blockchain.

How to Use Risk and Resilience to Help Your Decision-making

If a risk can be identified, then the risk can be planned for; the response will make the logistics chain far more resilient. That means a plan is in place to minimize the risk and to find ways to overcome it with minimal or at least fewer problems than would happen without this preparation. The solution may be ensuring long term contracts with multiple carriers from different countries to spread the risk, thereby removing the dependance on a single country and single provider. The solution may be extended to multiple warehouse providers to store goods in different parts of the world so they can be moved into areas affected by any risk that disrupts the supply.

The primary decision tool is the ‘total cost of ownership’ calculation, which will show the financial value among different logistics modes and solutions. But when the final selections are difficult to differentiate, risk becomes a factor. To put this into a defined and structured method, the overall risk factor can be made up of the identified risk and its impact.

Using the four categories of risk, each alternative can have the risks defined and each one’s level of impact. This is not an exercise in defining every risk, but it is a consensus of which risks are larger and more likely to significantly impact the capability to deliver the goods. Consider as an example – fictitious – the following scenario of sourcing goods from Venezuela or from Canada. If the TCO for these is similar, then the risks may offer the solution with the lowest TCO and lowest risk. The delivery from Venezuela could be faced with U.S. sanctions, political unrest, delays due to social problems, and/or activism, while Canada is probably more associated with strikes and delays due to weather. A more formal method of deciding on the risks and the impact is required, so all parties are involved and aware. These factors are chosen merely to illustrate the risk calculation. We will characterize the risk and impact on a scale of 1 to 3 for ease of use.

Venezuela

Sanctions (Risk 2, Impact 3)

Political Unrest (Risk 3, Impact 1)

Social Issues (Risk 1, Impact 2)

Activism Against the U.S. (Risk 2, Impact 1)

Total = 13

Canada

Strikes (Risk 2, Impact 2)

Weather (Risk 2, Impact 1)

Total = 7

It becomes evident in this simple example that with the TCO being very similar, the risk is potentially (at least from this fictitious example) significantly higher for sourcing from Venezuela than from Canada, and the result should be to choose the source with the lowest risk. It also identifies the risks, and it is incumbent on the logistics manager to ensure that the risks are planned for and minimized.

The highest risk factor is that of sanctions. In this fictitious example, a score of ‘6’ means this is a situation that the company must have defined plans for, and everyone needs to be aware of the actions necessary to overcome this situation. In addition, there must be a definitive effort to gain faster information should these sanctions become probable, so the plans have more time to be implemented. This type of assessment, planning and preparation will stand any company in good stead as it tries to negotiate global impacts on its business.

Conclusions

No management can eliminate all risk, nor should they as this is too large a cost and a detraction from the business. The proponents of the strategic review of SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) often talk about minimizing the weakness, but what is required is to reduce it so it is not a significant issue, and the company is resilient enough to overcome the situation should it arise. The ability and capability to deal with the particular risk which has been foreseen and where the response has been prepared with measured actions, means the company is faster, more agile and capable to weather the risk than its competitors, and that gives them a competitive advantage for a short period while other companies are trying to fix the issue(s).

Do you have an Incoterms experience to share that you'd like John to comment on and that could be included in a future article? Submit to Breakbulk's Leslie Meredith at [email protected] and include description, locations (origin and delivery), Incoterm used and lesson learned if applicable.

MAIN PHOTO: AAL transporting A-Class Blades on MPV AAL Newcastle. CREDIT: AAL Shipping