Region Needs More Development to Offset Production Declines

By Simon West

By Simon West

In a feature from Issue 5 of Breakbulk Magazine, we look at the challenges facing new natural gas developments in Latin America, and how Argentina is investing in infrastructure to ensure shale production at its prolific Vaca Muerta formation continues to flow.

Argentina’s surging shale production at Vaca Muerta and the buildout of supporting infrastructure such as pipelines, processing plants, export terminals and fracking equipment continue to provide breakbulk with a steady stream of cargo-carrying opportunities.

DHL Global Forwarding has been transporting cargo to and from Vaca Muerta since output began at the 30,000 square-kilometer oil and gas formation in the prolific Neuquen Basin in western Argentina more than a decade ago.

Earlier this year, the German-headquartered forwarder shipped a rig for one of its main customers from the Port of Corpus Christi in Texas to the Argentine port of Bahia Blanca in Buenos Aires province.

According to Pablo Hanacek, head of industrial projects at DHL Global Forwarding Argentina, some 112 pieces weighing a combined 1,515 tons were successfully delivered in a job that took 60 days to complete. The scope of the project included packing, transport to the port terminal, reception, and the loading and unloading of cargo at Bahia Blanca.

Nabors Argentina then hauled the cargo cross-country to the construction site.

“DHL Global Forwarding was the first to utilize Bahia Blanca as a port of entry for the industry, generating not only cost savings but also shortening the mobilization time for heavy equipment,” Hanacek told Breakbulk.

Support for Vaca Muerta

Logistical challenges that have threatened to derail development at Vaca Muerta – home to the second-largest shale gas reserves in the world and the fourth-largest unconventional crude reserves – are being tackled head-on by the government, state energy producer YPF and private sector players.

A first section of the state-funded Nestor Kirchner Gas Pipeline, or GNK – also dubbed the Vaca Muerta Pipeline – was commissioned in June this year. The 580-kilometer duct will eventually ship 22 million cubic feet of gas per day, or mcfd, from Tratayen in Neuquen province to compression facilities at Salliquelo in Buenos Aires province.

A second section of the GNK will extend the pipeline a further 470 kilometers to San Jeronimo in central Santa Fe province, where it will connect to the Northeast Gas Pipeline, or GNEA. YPF has also pledged to invest in more pipelines in the Vaca Muerta region, while a proposed 25 million-ton-per-year liquefied natural gas, or LNG export terminal at Bahia Blanca operated by YPF and Malaysia’s Petronas is slated to come online in 2032.

.jpg) “The sector has always demonstrated its capacity to be very creative and entrepreneurial when it comes to logistics needs,” Hanacek said. “The country’s gas related projects that will take place are not only linked to extraction but also to LNG plants, fertilizers and other developments. Of course, this is very exciting news for the future, and DHL is already working to support those projects.”

“The sector has always demonstrated its capacity to be very creative and entrepreneurial when it comes to logistics needs,” Hanacek said. “The country’s gas related projects that will take place are not only linked to extraction but also to LNG plants, fertilizers and other developments. Of course, this is very exciting news for the future, and DHL is already working to support those projects.”

Investment meanwhile continues to flow into E&P projects. In June, the Argentine government said Chevron would spend more than US$500 million to develop the 283-square-kilometer Trapial block, one of several fields the U.S. energy company operates in the region.

Other players to have plunged significant resources into the formation include YPF, Petronas, Shell, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, Wintershall and Mexico-based Vista Oil & Gas.

Argentine state news agency Telam said in July that a combination of higher oil exports – projected to reach US$25 billion over the next five years – and lower natural gas imports due to rising domestic production could reduce Argentina’s energy deficit to zero this year – quite a turnaround following last year’s shortfall of nearly US$5 billion.

Natural Gas Wins

Vaca Muerta though could be one of just a handful of bright spots in the region’s natural gas sector, a surefire source of work for breakbulk and project cargo.

Less-polluting than other fossil fuels, natural gas has been deemed a “bridge fuel” in global energy transition. The Latin American Energy Organization, or Olade, said in a recent white paper that there was a “window of opportunity” to monetize Latin America’s rich natural gas resources and provide “quick wins” consistent with decarbonization objectives.

According to Olade, the region’s largest economies – Brazil, Mexico, Argentina and Colombia – show no sign of ditching the use of natural gas in their energy systems. The share of gas in Latin America and the Caribbean’s total primary energy supply by 2050 is expected to oscillate between 21 percent and 30 percent.

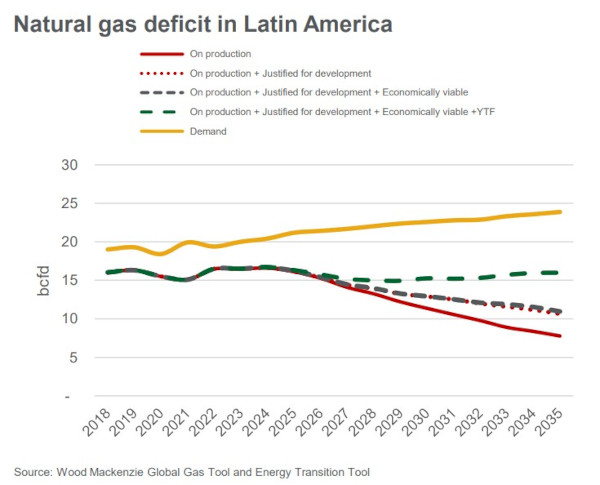

In another recent report, consultancy Wood Mackenzie predicted gas demand in Latin America would increase by 1.4 percent per year over the next decade, stabilizing at about 25 billion cubic feet per day, or bcfd.

Demand would be driven mainly by industrial use and power generation, the report said.

But as new gas developments throughout the region face challenges ranging from infrastructure restrictions and unfavorable exploration incentives, supply is set to decline at a rate of 5.6 percent over the period, driving the need for more imports to cover the shortfall.

According to the consultancy, without more upstream developments, net imports in the region could double to 12 bcfd by 2035.

“Argentina is the only Latin American country expected to add significant supply from undeveloped contingent resources. Through requested bids, the government has addressed the lack of infrastructure to evacuate increasing gas volumes from the Vaca Muerta area, and the Nestor Kirchner pipeline seems to be on track for reaching phase 1 expected capacity,” Adrian Lara, principal analyst at Wood Mackenzie, said to Breakbulk.

Challenges for Some

Other nations covered in the Wood Mackenzie report face tough challenges to either maintain or boost output.

“In the medium term – the next five years – there might be increased activity in Trinidad and Tobago if they manage to jointly develop with Venezuela fields which are nearby or share a maritime border with Venezuela,” Lara said.

“This, however, is all subject to successful negotiations with the Venezuelan government which in turn requires that the U.S. government eases the sanctions imposed. Venezuela itself has the largest undeveloped gas discoveries in the region, but their development is still challenged by infrastructure constraints and above-ground issues.”

Peru, one of Latin America’s two LNG exporters – the other being Trinidad and Tobago – boasts the prolific Camisea field in the country’s Cusco region. Undeveloped resources in Camisea account for about 3.7 trillion cubic feet, or tcf, but development has been postponed due to regulatory hurdles and a lack of additional pipelines to the south of the country.

Peru, one of Latin America’s two LNG exporters – the other being Trinidad and Tobago – boasts the prolific Camisea field in the country’s Cusco region. Undeveloped resources in Camisea account for about 3.7 trillion cubic feet, or tcf, but development has been postponed due to regulatory hurdles and a lack of additional pipelines to the south of the country.

In Colombia, new developments in offshore areas would depend on the country’s leftist government led by President Gustavo Petro allowing for additional exploration and reducing the uncertainty of exploiting hydrocarbon resources.

“The new administration had threatened to end all future exploration, although in practice nothing has changed drastically yet,” the analyst said.

Brazil, meanwhile, whose massive pre-salt hydrocarbon boom has also called for significant project logistics support, approved in 2021 a new gas law designed to attract fresh investment into the sector, eliminate barriers to competition and reduce energy prices.

For years, the sector has been dominated by Petrobras, which still accounts for about 70 percent of domestic gas production.

The state energy giant – which found itself at the center of a multi-billion-dollar cash-for-contracts scandal last decade that briefly threatened to derail its pre-salt drive – remains the operator of some of Brazil’s most prolific gas fields, such as Mero, Tupi and Buzios in the Santos pre-salt province off the coast of Rio de Janeiro.

“The changes made in 2021 were a great milestone to foster investments from other companies, to create market liquidity and develop infrastructure,” said Rafael Cristelo, the Sao Paulo-based general manager of “K” Line Brasil, part of Japanese shipping company Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, or “K” Line.

“Of course, it will take time until we see a truly competitive market. Incentives, like special tax regimes and lower financing costs, will speed up this process.”

Brazil Pessimism Surfaces

Other project professionals speaking to Breakbulk were not so bullish.

“We still cannot see major progress or impact on the prices as the legislation has not been fully implemented,” said an executive working in Brazil’s oil and gas sector.

“The main issue is the planning in view of the historical uncertainties in Brazil, so most companies are still waiting to see how things progress to be more on the safe side prior to them taking any actions or making investments,” added the executive, who asked not to be named.

Another key challenge for Brazil is building the infrastructure to support production.

Delays to complete the construction of major projects such as the 355-kilometer Rota 3 pipeline that would transport up to 18 million cubic meters of gas per day from the Santos Basin to Petrobras’ Gaslub natural gas processing plant in Rio de Janeiro have been blamed for lower gas availability.

Originally slated for start-up in 2019, the pipeline, which comprises a 307-kilometer offshore section and a 48-kilometer onshore section, is now expected to begin full operations in 2024.

“Infrastructure in Brazil is always a key issue, and there is still a lot to be done,” the executive said. “This involves high levels of investments and risks which once again depend on a better scenario, regulatory issues and legal certainty. In any case, a better gas network has to be installed and part of the existing one must be refurbished.”

Bolivia’s Struggles

Bolivia, one of Latin America’s three largest gas-producing countries alongside Argentina and Peru, and the region’s main gas exporter, is struggling to revert production declines that began almost a decade ago.

Furthermore, dwindling reserves and a lack of finances threaten the Andean country’s long-held ambition to build a series of world-scale petrochemical production plants. State-controlled energy company YPFB, alongside its industrial division, EBIH, had unveiled plans to build more than a dozen plants for polyethylene, polystyrene, aromatics, methanol and other petrochemical production.

To date, just one project has been brought online – the Bulo Bulo urea fertilizer plant in central Cochabamba Department. One Bolivia-based project professional told Breakbulk that power generation and agribusiness had overtaken hydrocarbons as the key sectors for project cargo.

“The decline in Bolivia’s gas production could have a drastic impact on its exports, and without additional discoveries, the decline will not be reversed. It is possible that, by the end of the decade, Bolivia will only be producing enough gas to meet domestic demand,” Wood Mackenzie said.

“The main change in the subregion is the potential role of Argentina in supplying gas to its neighboring countries. It is not without its challenges, however, amid the persistence of above-ground issues such as energy policy changes and macroeconomic instability.

“Still, it has the potential to replace Bolivia as the key regional exporter.”

Latin America’s project market will be the focus of a mainstage panel session at Breakbulk Americas 2023. “Latin America Spotlight: Outlook, Projects and Opportunities”, moderated by Fox Brasil’s Murilo Caldana and featuring expert speakers from Tradelossa, DHL Global Forwarding, Port of Açu and Valaris, will take place on September 27 from 1:20pm–2:10pm.

Check out the full main stage agenda for this year’s event, happening on 26-28 September at the George R. Brown Convention Center in Houston, Texas.

PHOTO CREDIT: DHL Global Forwarding