Jan 21 | 2022

China’s Space Program Offers Project Potential

By Thomas Timlen

Now underway in earnest, China’s International Lunar Research station development is providing a space race boost for regional project cargo.

Now underway in earnest, China’s International Lunar Research station development is providing a space race boost for regional project cargo.The developments drawing most attention to China of late predominantly relate to territorial grabs in the South China Sea and the soft power influence China is applying with the Belt and Road Initiative. China’s space ambitions have received comparatively less attention, including the plans to establish bases on the Moon that already have secured collaboration with Russia’s space agencies. Those overlooking these developments run the risk of missing the potential opportunities that may arise for project cargo transportation here on Earth.

In June the China National Space Administration released the details of the International Lunar Research Station, or ILRS, Guide for Partnership, a framework involving four phases of space exploration, orbital space stations and lunar bases, all taking place from 2021 to 2045, and all aimed at the ultimate goals of lunar exploration and eventual exploitation of resources that might be found beneath the lunar surface. Transportation of such resources from the Moon to the Earth is the overarching aspiration should the plans succeed.

Throughout the scope of these works the movement of personnel, equipment and supplies will require spacecraft for delivery and transport systems, which in turn require extensive support systems and administration, funding, training and launch facilities.

Describing the ILRS as ambitious would be an understatement. A review of the details within each of the four planned stages raises questions regarding the potential expansion of traditional logistics and project cargo operations from established routes on terra firma to cosmic lunar voyages, an initial baby-step preceding what eventually could lead to intergalactic logistics opportunities. Closely following the brief spaceflights arranged by a trio of wealthy enthusiasts, the potential for tangible short- and long-term opportunities for the transport sector cannot be ignored.

Lunar Possibilities

Gearing up to meet the transportation needs that might avail themselves should there be a demand for moving bulk quantities of lunar resources down to Earth post-2045 might be premature. However, an evaluation of the near-term potential opportunities generated by China’s ambitious plans does warrant attention, as these can be met with the deployment of existing logistics assets.

Gearing up to meet the transportation needs that might avail themselves should there be a demand for moving bulk quantities of lunar resources down to Earth post-2045 might be premature. However, an evaluation of the near-term potential opportunities generated by China’s ambitious plans does warrant attention, as these can be met with the deployment of existing logistics assets.Although the final assembly of spacecraft is presently done at the respective launch sites, there will be opportunities involving the transport of rocket and spacecraft components from places of manufacture to the respective launch site assembly facilities. In addition, there are indications that additional launch sites will be constructed to maintain adequate capacity for the increasing frequency of launch activity. In this respect, providers of project cargo services stand to benefit not only from the opportunities surrounding the construction of new launch sites, but also from the demands that will arise for the development and expansion of related infrastructure supporting the new launch sites that will span from road and rail to bridges and seaports.

Speaking to Breakbulk, Professor Bernard Foing, executive director at the International Lunar Exploration Working Group, or ILEWG, agreed that the plans to construct new launch sites throughout China will create many opportunities in the project cargo transportation sector.

Speaking to Breakbulk, Professor Bernard Foing, executive director at the International Lunar Exploration Working Group, or ILEWG, agreed that the plans to construct new launch sites throughout China will create many opportunities in the project cargo transportation sector.Foing speaks with confidence as the ILEWG is a public forum initiated in 1994 and sponsored by several of the world’s space agencies to support international cooperation towards a world strategy for lunar exploration and utilization. Active participants include NASA, China’s National Space Administration, China’s ILRS partner Russia, Roskosmos, together with several European space agencies and their Japanese and Australian counterparts.

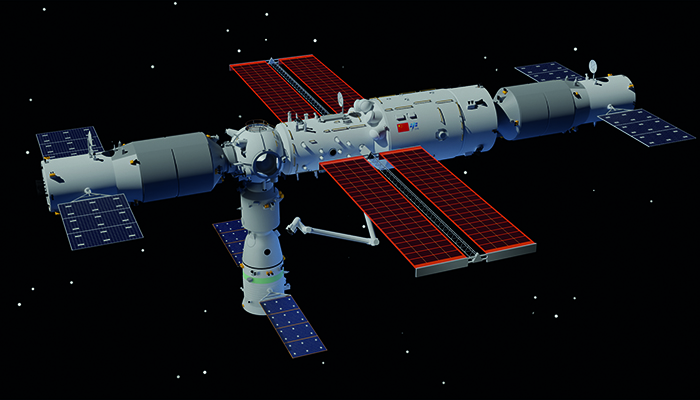

Foing saw no reason to doubt China’s ability to construct a station on the moon, pointing to China’s progress with its Tiangong space station, expected to be completed in 2022. “The Chinese Space Station is completing its initial construction goals as planned in 2022, with the Modular Space Station Experiment Module I Wentian ‘Quest for Heavens’ launch planned for May or June 2022. The Modular Space Station Experiment Module II Mengtian ‘Dreaming of Heavens’ launch is planned for August or September 2022 and a separated space telescope module Xuntian ‘Touring the Heavens’ has its launch planned for 2024.”

Foing’s optimism is shared, although with a caveat, by another subject matter expert, Andrew Jones, a correspondent with SpaceNews, who has been closely monitoring developments. “China has demonstrated that it is able to set long-term plans and, through gradual accumulation of technologies and experience and building on earlier successes, deliver on these and develop new capabilities.

Foing’s optimism is shared, although with a caveat, by another subject matter expert, Andrew Jones, a correspondent with SpaceNews, who has been closely monitoring developments. “China has demonstrated that it is able to set long-term plans and, through gradual accumulation of technologies and experience and building on earlier successes, deliver on these and develop new capabilities.“We can see that China is working on the elements needed to get humans to the Moon and back, new super heavy-lift launchers, a deep space-capable spacecraft, a lunar lander and the profile of the Chang’e-5 sample return mission, and appears serious about carrying out such a mission. This is a challenge in terms of technology and funding, however, and while progress appears good, failures or external events could prove problematic, as with any country’s space endeavors.”

Spaceport Progress

Currently, the Chinese space program relies on four existing launch sites, three well-inland at Jiuquan, in Gansu province; at Taiyuan, in Shanxi province; and at Xichang, in Sichuan province. The fourth and newest spaceport is the Wenchang Space Launch Site in Hainan province. Previously only used for sub-orbital launches, Wenchang was subsequently upgraded and was recently the location for the launch of the Tianzhou-2, a Chinese cargo resupply ship launched in May to dock with the Tiangong space station, presently under construction while in orbit.

“Wenchang is looking to build a space ecosystem in connection with the launch site,” Jones said. “This would include commercial launch companies launching their rockets from Wenchang, including potential sea recovery platforms for reusable first stages, in a similar fashion to SpaceX’s use of drone ships for Falcon 9 first stage landings.”

“Wenchang is looking to build a space ecosystem in connection with the launch site,” Jones said. “This would include commercial launch companies launching their rockets from Wenchang, including potential sea recovery platforms for reusable first stages, in a similar fashion to SpaceX’s use of drone ships for Falcon 9 first stage landings.”Additionally, an “Eastern spaceport” is being developed at Haiyang, Shandong province on the east coast for facilitating sea launches. A couple of sea launches have been carried out using a converted barge, but a new, dedicated vessel for sea launches – and potentially for landing stages – is being constructed and is expected to come into service in 2022. “This would provide another outlet for China’s growing launch sector, for both state-owned solid Long March rockets, solid rockets from a commercial spinoff named China Rocket, and potentially others such as CAS Space and Landspace,” Jones said.

With respect to the logistics network connecting manufacturing sites and assembly facilities at the launch sites, Jones explained: “The China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation has two main rocket developers and manufacturers under its ownership, with one in Beijing (CALT) and the other in Shanghai (SAST). The old generation Long Marches are delivered from these centers via rail, to Jiuquan, Taiyuan and Xichang.”

Some satellites are delivered to an airbase near Xichang for those missions, which are usually launches of larger satellites to geostationary orbits, he added. Some of the newer rockets, namely the Long March 5, 7 and 8, are manufactured under CALT in the northern port city of Tianjin. The components and stages of these rockets are delivered to Wenchang on the southern island of Hainan via cargo ships, in part because the rail infrastructure cannot handle the large, 5-meter-diameter core stage of the Long March 5. Work on assembly, integration and testing of the rockets takes place in a large vertical integration building at Wenchang spaceport.

Infrastructure Pros and Cons

One feature of the Wenchang Space Launch Site in Hainan is that spacecraft and related components arrive at its seaport. Therefore, the Wenchang seaport could provide opportunities for heavy-lift vessel operators to provide project cargo services.

In contrast, the other three inland launch sites are served by rail. The respective tracks are reportedly too narrow to facilitate the transport of new 5-meter core rocket boosters. Whether the tracks will be upgraded, or whether roads will be constructed to facilitate road haulage of the boosters remains to be seen.

Whether the road or the rail systems are upgraded, logistics professionals based in China do not see immediate opportunities for non-Chinese project transport providers hoping to provide services relating to the movement of components for spacecraft or rockets, as this is now predominantly reserved for state-owned companies. On the other hand, opportunities can be expected relating to the infrastructure improvements and launch site construction works that are anticipated.

Meanwhile, the potential opportunities for project cargo transport providers that the ILRS could generate are not limited to domestic Chinese movements. The decision by Russia to accept China’s partnership offer to be involved with several ILRS phases opens the door to potential cross border movement of Russian and Chinese rockets, spacecraft and related supplies and equipment as the ILRS has provisions for the use of Russian rockets transporting Chinese spacecraft into orbit and vice versa. Russia’s Vostochny Cosmodrome north of the Chinese border could be one location likely to receive spacecraft and/or propulsion units from China.

Such cross-border movements might be long term, although there may be short-term opportunities for providers of air transport, as Foing explained: “At the moment it is more effective to launch spacecraft from countries where they have been produced. Otherwise, current spacecraft are still of limited size and can use existing transport infrastructures, including large cargo planes.”

Partner Opportunities

Looking ahead, routes that could facilitate movements between Chinese and Russian launch, assembly and manufacturing sites may be found along the ever-expanding Belt and Road Initiative, or along existing routes such as the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor and the New Eurasia Land Bridge Economic Corridor. Road haulers with existing services along these routes may reap the initial benefits, while others could see new opportunities arise as the BRI is expanded to meet new demand stemming specifically from ILRS-related movements in addition to trade volumes in general. There may also be a need for air freight services to transport related spare parts, smaller components and time-sensitive equipment.

Should other countries follow Russia into ILRS partnership with China, demand for transport services will in turn expand along with traffic along these corridors, while ocean transport providers could similarly gain from the involvement of Asian and APEC countries as ILRS partners. While some cargo would require the services of project cargo transporters, other partner countries will only require conventional shipping services. Singapore, for example, has proven to be a proficient producer of miniaturized satellites, which can be shipped in conventional containers.

Should other countries follow Russia into ILRS partnership with China, demand for transport services will in turn expand along with traffic along these corridors, while ocean transport providers could similarly gain from the involvement of Asian and APEC countries as ILRS partners. While some cargo would require the services of project cargo transporters, other partner countries will only require conventional shipping services. Singapore, for example, has proven to be a proficient producer of miniaturized satellites, which can be shipped in conventional containers.Will the ILRS partnership grow to include countries other than China and Russia? Foing pointed to existing collaborations with several nations that bode well for such an expansion: “There are countries that are collaborating with China on the lunar and planetary robotic exploration program. There are also contributions to the Tiangong Chinese space station. China is conducting bilateral cooperation and exchanges with France, Italy and other countries on the Tianhe space station experiments in the fields of basic physics, space medicine and space astronomy. That is significant for strengthening cooperation on the space station, and to conduct new science. These experiments could have a natural follow-up with the ILRS program.”

Some of these countries are also contributing to the U.S.-led Artemis program, Foing added. Also, since 2016, China has cooperated with the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. Here, China has invited all UN member states to participate in cooperative experimental projects related to the Chinese space station. To date, nine projects from 17 countries have been selected. These cover a wide range of scientific fields, from astrophysics, microgravity physics and biology to mid-infrared Earth observations and gallium arsenide semi-conductor and microphase cooling technologies.

In less technical terms and with a more conservative outlook, Jones sees potential for more nations to join the ILRS initiative, but not without challenges. “China and Russia are attempting to court a number of space actors, but the main interest appears to be securing involvement at some level of European nations such as France, Germany, Italy and so on, which have great technology capabilities and experience in exploration and human spaceflight.

“The pair (China and Russia) are developing frameworks for involving partners in the ILRS and talks are ongoing, but those involved are reluctant to state their positions and deliberations will need to take place with a number of stakeholders. It’s complicated, particularly given the current geopolitical context.”

Thomas Timlen is a Singapore-based analyst, researcher, writer and spokesperson with 31 years of experience addressing the regulatory and operational issues that impact all sectors of the maritime industry.

Photo 1: 3D rendering of China’s cargo spacecraft Tianzhou-2 which will later docking with Tianhe – the Core Module of China’s Modular Space Station. CREDIT: SHUTTERSTOCK

Photo 2: Bernard Foing, ILEWG

Photo 3: Andrew Jones, SPACENEWS

Chart: Launch sites and manufacturing locations

Photo 4: Rendering of Tiangong Space Station in October 2021, with the Tianhe core module in the middle, Tianzhou-2 cargo spacecraft on the left, Tianzhou-3 cargo spacecraft on the right, and Shenzhou-13 crewed spacecraft at nadir. CREDIT: SHUJIANYANG, WIKEMEDIA, CC BY-SA 4.0

Photo 5: An International Moonbase Alliance simulated deep space mission on Earth. Credit: ILEWG